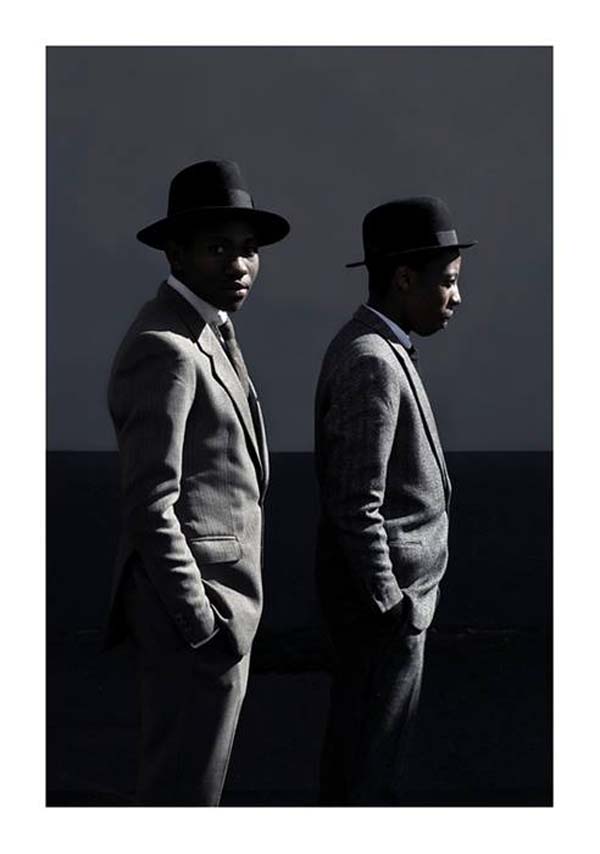

THE SARTISTS: NOSTALGIA FOR THE SUIT

The Sartists are a couple of “sartorial-artists” from Johannesburg who have been enjoying significant visibility worldwide since appearing in a Coca-Cola commercial in 2013 and on the South African trendsetting page Flux. Their style mixes vintage and contemporary elements, in the fashion of gentleman revivalism made popular by Sam Lambert and Shaka Maidoh of Art Comes first. In their blog, the Sartists collect visual cues of a nostalgic reworking of classic black style as represented, most iconically, by the suit, the quintessential costume of black dignity and respectability.

Whether destructured,

matched with a duffel or hand bag,

or worn with a roll neck in its two-piece variety,

The suit creates the peculiar short-circuit of past and present that is the core of nostalgia. It calls back to the politics of costume adopted by black South Africans during the apartheid, as well as to the African-American strategies of ‘stylin’, in both cases functioning as a performative sign of self-worth and racial pride.The variety of hats that accompany the suits further establishes this nostalgic discourse, which the Sartists pursue by posting dedicated features about inspiring sartorialists such as Nelson Mandela, Patrice Lumumba and Marcus Garvey. In a post on entitled “Politicians that inspire”, they celebrate the Black Conscious Era, contending that it was a defining moment in the development of a pan-African fashion consciousness. This was when “the Black man took pride in his appearance.”

“400 years of Black Slave Ancestors picking the cotton but not wearing it.”

Thus, the Sartists appropriate the suit+hat as the main referents of a remake of what they call “Township Elegance”. In a post about the Apartheid Secret meetings, they express a commitment of “bringing back some History they forgot to tell you in your History class”. And indeed, they maintain that their style is “not only about the clothes. It’s about Life. Struggle. Expression. Art. History. Love.”

The same desire to disclose the unwritten history of African sartorial resistance through a nostalgic revival of 1950s urban style recurs in the words of Loux the Vintage Guru, another emerging star of African dandyism, who claims to wear vintage hats and ties out of respect for “the legendary era of [his] ancestors”.

Since I began researching African dandyism, I have looked for cues of what distinguishes it from its British and North American incarnations and had trouble collecting them. Sure these varieties have a lot in common, as Monica Miller shows in Slave to Fashion, most notably their affirmative goal, but there is also much more to unpack that makes stylists like The Sartists and the Vintage Guru profoundly and unmistakably African. I believe that their appropriation and reworking of the past, particularly the years of the late colonialism/early independence, could put me on the right track.