THE KANGA: MODERNITY, CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION AND CULTURAL TRANSLATION IN COLONIAL ZANZIBARI FASHION

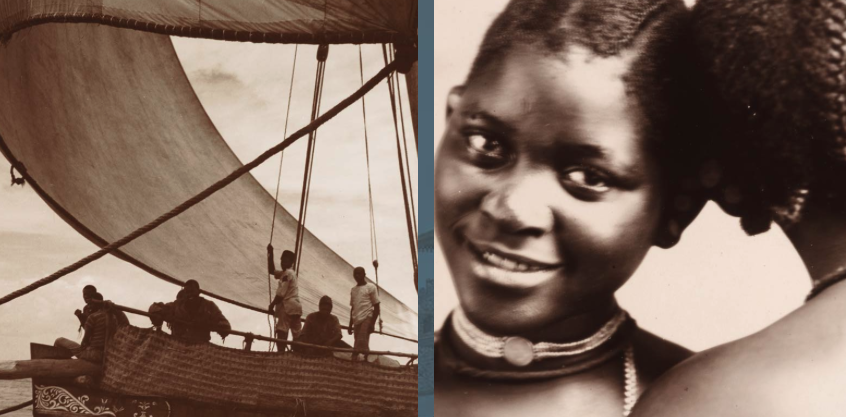

Last week I stumbled upon the online exhibition Sailors and Daughters: Early Photography and the Indian Ocean curated by Erin Haney, which exhibits photographic documents from the early 20th century of the everyday lives of the maritime societies of East Africa, the Persian Gulf and other Indian Ocean ports.

This is a notable curatorial work for many reasons, not least because it shares material that is rarely available to the general public. The lending institutions include archives, libraries, and collections: the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives and the Warren M. Robbins Library at the National Museum of African Art; the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies Winterton Collection, the Stephen Arpee Collection of Sevruguin Photographs, Archives départementales de La Réunion and Iconotheque de L’Ocean Indien, the Seychelles National Archives, and the Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

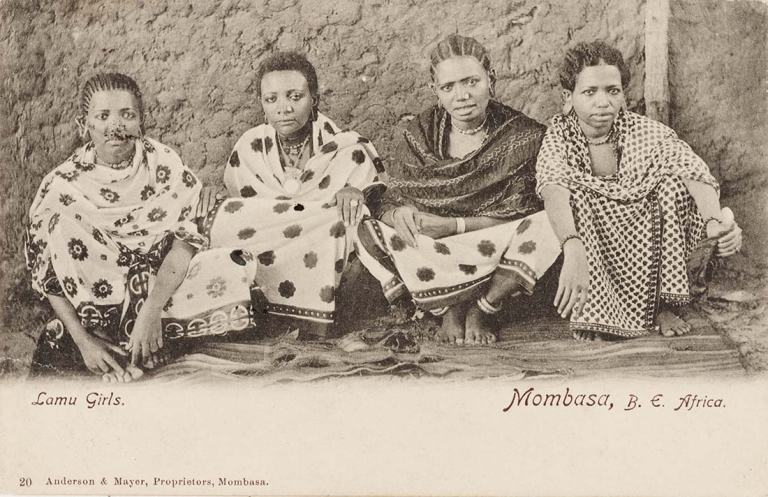

My reason for writing about it are the portraits of Zanzibari women included in the section “Swahili Coast Daughters” which are a useful resource on East African dress and ornamentation. All the photographs show the women wearing sumptuous kangas: the printed, multi-purpose cotton-piece good (worn also by men) that is a staple of female fashion throughout East Africa. The garment signals that the women are emancipated slaves and references their economic power. The look of the apparels and the wealth of accessories that complement them suggest that the cloths are imported and therefore the women’s idea of a modernity, as something that had to be displayed, embodied, and performed.

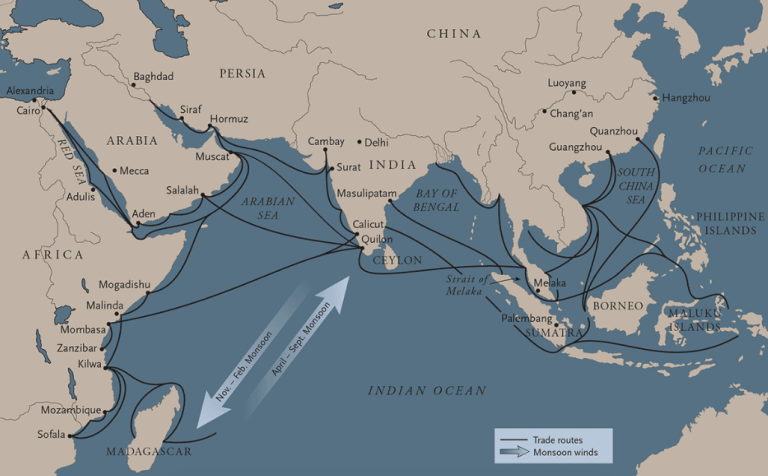

Examined in the context of an exhibition about colonialism in the Indian Ocean region, these studio portraits and postcards link the spectacle and wonder of modernity to intersecting stories and routes of migration, uprooting, relocation, and dispossession (Chambers 1990). “Consumption, particularly of imported goods, became an important social marker of cosmopolitanism for members of this generation, demonstrating both their relative wealth, compared to their parents and other East Africans, and their location at the center of the transnational flow of goods and ideas between East Africa and the wider world” (Fair 2004, p. 20).

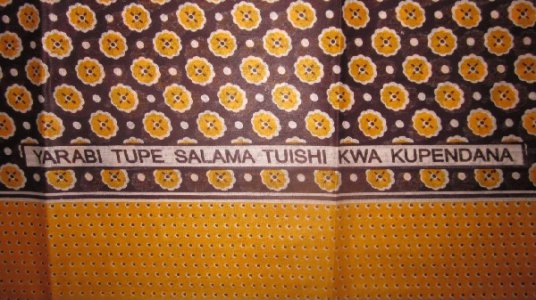

The kanga encapsulates this syncretic nature of modernity since, like the textiles in vogue in other regions of Africa, most notably the West African ankara/wax cloth that I examine in another post, it too wasn’t produced locally (at least in late 1800s, early 1900s — today it is a relevant component of the local fashion economy). The glamorous items shown in the pictures came most likely from Britain and the Far East, whereas the very first kangas were fashioned from the pure-cotton cloth sold by Portuguese traders. The text messages and proverbs in Swahili printed at the bottom of each piece (majina and methali), as well as the name kanga, that refers to a colorful guinea fowl,* inscribed these goods into local cultures, creating an aesthetic that made cultural translation (but really global exploitation and dispossession of manpower and raw materials by colonial powers) manageable (in both literal and metaphoric sense — the cloths were/are usually cut and fashioned in two-piece ensembles, wrapped around the body, or stripped to create baby slings) and desirable, with each majina and methali carrying a different message the cloth’s owner related to and wanted to share.

The translation continues today with the textile inspiring both locally-produced traditional and streetwear fashion.

* Other scholars maintain that kanga derives from the Arabic “khanqa”, or cloth.

Bibliography:

Chambers, I. (1990), Border dialogues: journeys in postmodernity, Oxon: Routledge.

Fair, L. (1996), ‘Identity, difference, and dance: Female initiation in Zanzibar, 1890 to 1930’, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 146-172.

Fair, L. (1998), ‘Dressing up: Clothing, class and gender in post-abolition Zanzibar’, The Journal of African History, 39(01), 63-94.

Fair, Laura, ‘Remaking Fashion in the Paris of the Indian Ocean: Dress, Performance, and the Cultural Construction of a Cosmopolitan Zanzibari Identity,’ in Fashioning Africa: Power and the Politics of Dress, Jean Allman (ed.), Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

Lichtenstein, A. L. (2011), ‘Stitched secrets, public poetics: My obsession with kanga text/iles in East Africa’, Contrary Magazine, 23 March, <http://blog.contrarymagazine.com/2011/03/stitched-secrets-metaphor-in-motion-my-obsession-with-kanga-textiles-in-east-africa/>

McCurdy, S. (2006), ‘Fashioning Sexuality: Desire, Manyema Ethnicity, and the Creation of the” Kanga,”” ca.” 1880-1900’, The International journal of African historical studies, 441-469.

Ong’oa-Morara, R. (2014), ‘One Size Fits All: The Fashionable Kanga of Zanzibari Women’, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, 18(1), 73-96.