THE BLACK SELFIE: LOZA MALÉOMBHO’S #ALIENEDITS

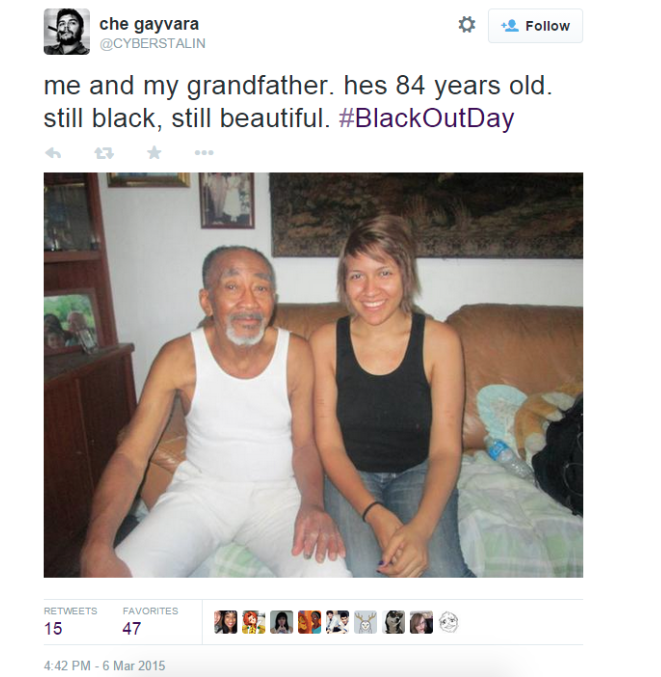

On March 6th, 2015 Tumblr and other social media hosted the first BlackOutDay to counter the notion that beauty is a whites-only affair. According to a statement published in the official page of the movement, on BlackOutDay black users “like and reblog selfies of each other and fill our dashboards with encouragement”. Since then, the day has been made seasonal, with the second event taking place on June the 21st and more anti-racist initiatives added to the agenda.

As a new instantiation of the “black is beautiful” motto, BlackOutDay is concerned with appearances, style, and self-presentation. Particularly, its message of racial pride is delivered via the selfie, a medium of self-representation that notoriously focuses on the face and facial expressivity.

The circulation, reblogging, sharing, and commenting of tens of thousands of pictures that has been going on since March on social media is proof of the urgency with which black subjects engage the global visual culture as a space to produce a nuanced narrative of blackness. With Black Twitter as a channel of networking and contagious opinion-making across racial lines (Sharma 2013), the black selfie expresses the desire to make racial embodiment a part and indeed a framework to experience and address our digital selves. The use of the selfie in visual activism is rising especially among racial minorities, who practice DIY photography and photo-editing to “fashion alternative public visibilities” (Pham 2015: 232). Typically set in public and/or anonymous locations, like bathrooms and bedrooms, these shots reference the everyday, the accidental, and even the unglamorous, contributing to normalize perceptions of a supposed threatening, abject, or abnormal diversity. In its self-referentiality the selfiescape inspired by BlackOutDay also wishes to foreground the diversity inherent in blackness, making space to represent minorities within the macro-minority of blackness like LGBTQ users, users with disabilities, etc.

In effect, BlackOutDay is a vernacular and collective effort to counteract the bias of racialized profiling that is inherent to mainstream visual and popular culture where blackness is often linked to abnormality, of one sort or another – be it the disenfranchisement of black Americans, or the state of perpetual ‘need’ and ‘exception’ of Africans in their home countries and abroad. On some occasions, selfies have been prominent weapons of the fight for social justice. In the trial for the murder of Trayvon Martin, the defense used pictures that Martin had posted on social media as evidence of his ‘suspicious’ lifestyle, whereas for his family and the millions worldwide who took the side of the innocent victim one selfie in particular became the symbol of his lost innocence. According to Nicole Fleetwood (2015), Martin’s selfie has become a powerful catalyst because it operates as a racial icon that “conveys the weight of history and the power of the present moment, in which […] his presence marks the historical moment” (unpaginated, Kindle edition). Like other icons, the selfie distills conflicting tensions and turns them into a narrative with the power to generate attachment and prompt action. More importantly, it shows the power of blackness to arrest and hold attention within a image-saturated culture. “[T]he justice for Martin protests speak to the changing perception and reception of the icon and what it means to have ‘staying power’ in a cultural climate where the consumption of images occurs more often involuntarily and with such rapidity that it makes it challenging to hone in on a singular image” (Fleetwood 2015, id.).

Yet, in Trayvon Martin’s story, the selfie is a tool of self-documentation that was only posthumously mobilized to political ends. In this sense, the tension between public and private, boy and citizen, that infuses Martin’s selfies acquires a different value and currency with death. It is up to those who are affected by his story to comment and keep alive the fight for inclusion and justice. Among these is Loza Maléombho whose selfie portraits were inspired by the assassination of Michael Brown in Ferguson. Maléombho is a black reasporan designer: born in Brazil, she studied fashion in New York and relocated to Cote d’Ivoire where she currently runs a shop and online e-commerce selling her creations.

Recently, Maléombho has gained some online fame for her series of self-portraits entitled “#alienedits“. The selfies, which she routinely posts on her Instagram account, show her in profile, sporting African headwear, masks, and decorations of which she gives descriptions, filling her followers with information on African history.

Another shot, the selfie “N’Tomo” shows, again, Maléombho’s right profile as she holds another mask with a bun and leaf in her hair. The caption reads: “The N’tomo is organized into five year long grades through which boys must pass before their circumcision. The main principles of communal farming, judging disputes and protection against evil spirits are taught, as well as physical courage. N’tomo masks are said to be the most ancient. They appear as a human face with four to ten projections which, regardless of their actual number, are said to represent the eight primordial seeds made by God to create the universe. The specific number of spikes or horns indicates whether the mask is masculine, feminine or androgynous: in Bamana numerology, multiples of three indicate masculinity, four and eight indicate femininity and two, five and seven are associated with androgyny. #MALI”

“Peace, Love, and Drinking Water” is inspired, instead, by environmental issues. The selfie promotes sustainability in the continent:”‘Peace Love and Clean Drinking Water’ — Access to clean water is still an issue in rural areas of several countries in Africa. NPO @faceafricawater is working at changing that in Liberia. Today’s #AlienEdits is dedicated to you”

The designer describes the project to Le Monde Africa as a personal expression of African pride that she began to develop when she lived in the States. Africanness, in this sense, is filtered through the lens of post-diasporic blackness and imbued with the concern for visibility and recognition most strongly voiced by black Americans.

In another interview Maléombho states:

“’Alien Edits’ are socially conscious selfies expressed through style, pride, grace, and cultural awareness and against racial, class, cultural, religious and sexuality stereotypes, all of which cause a state of alienation on its victims. The recent US judiciary system’s discriminative decisions against African Americans such as in the case of Michael Brown in Ferguson as well as the lack of sensitivity from African governments towards human rights in the case of the 200 girls being kidnapped by Boko Haram in Nigeria, are most responsible for the series. I think the spark happened after the grand jury found Darren Wilson not guilty in the case of Mike Brown. The decision carried emotions of deep despair which I think were felt amongst African Americans and also Africans of the diaspora. While I empathised with sadness and anger on that day, I also felt deeply devalued, even alienated in some way. I needed to quickly eradicate those feelings for me and anyone like me by nurturing the exact opposite: Pride and self-validation. Ever since then ‘Alien Edits’ became a way to respond to current events, celebrate cultural diversities and traditions, and communicate with people of my generation.”

Most interestingly, she expands on the importance of self-composure, stressing the selfie’s semiotic power as a tool to channel black pride and fierceness.

“Alien Edits is an effort to bring awareness on social and cultural issues that affect people of my generation and empowers them with uplifting messages of grace, royalty, empathy and elegance in order to push upward. Some symbols include the stretching of the neck for stature and pride and the constant use of the hand as a key element of grace and self validation for example. So I thought: what better and faster way to communicate these ideas than with a selfie?”

In the above description, the black selfie becomes the weapon par excellence of a racial politics of self-representation and reclamation across national barriers. It provides not simply a content to counteract the lack of positive and diversified visual proofs of blackness, but becomes a framework to perceive as black and African, importing African popular and often unacknowledged cultures into the frame using the visual possibilities of vernacular, DIY photography to push a message of self-determination.

Bibliography:

Fleetwood, N. (2015), On Racial Icons: Blackness and the Public Imagination. New Brunswick: Rutgers

Pham, Min-Ha T. (2015), “‘I Click and Post and Breathe, Waiting for Others to See What I See’: On #FeministSelfies, Outfit Photos, and Networked Vanity”, Fashion Theory, 19.2: 221-242.

Sharma, S. (2013), “Black Twitter? Racial Hashtags, Networks and Contagion”, New Formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, 78.1, 46-64.