AFRICA LEADS WORLD’S GROWTH OF SUPER-LUXURY MARKETS

A few weeks ago, Bloomberg posted an analysis of Africa’s luxury goods market containing useful data to understand a core aspect of the “Africa rising” narrative: the rise of the super-luxury economy of fashion and accessories.

Citing projections by Euromonitor of a steady annual growth of Sub-Saharan GDP at 4-5% for the next five years, the study states that the continent is replacing Eastern Asia as the world’s fastest expanding market of luxury goods.With a population of wealthy individuals that has doubled in the past fifteen years, rising by 3% in 2014 alone, Africa’s ultra-wealthy population is forecast to further expand by 59% over the next decade. In particular, the highest concentration of this segment is found in Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire. According to The Wealth Report, the latter will expand its ultra-wealthy population by 119% over the next decade, while Nigeria is forecast to grow 90% over the same period.

Driving the growth of the market for exclusive products and services is the appetite of a burgeoning niche of male African millionaires for luxury fashion and accessories.

Demand for luxury watches, men’s clothing and leather goods in Africa is driven by the higher spending power of men. In South Africa, women have just 60% of the disposable income of men, according to Euromonitor. This means men’s clothing and leather accessories stores are already the second-most visible in the luxury segment. Fine watches and jewelry make up 25% of luxury stores. Gucci, Dior and Sergio Rossi are rare among luxury brands, in that they also operate single-brand female-collection only stores.

In particular, luxury watches figure as the top-rated commodity of African millionaires in a report by New World Wealth (a South African firm specializing in high growth market research) dated November 2015, which, again, emphasizes the gendered element of luxury consumption (countered, however, by this article citing a Delotte report on female-driven luxury growth in South Africa). According to this source, over the past 10 years, the global men’s watch industry “has grown by more than five times in terms of revenue, whilst in Africa it has grown by even more. As one local retailer put it: ‘watches have become to men what diamonds are to woman’”.

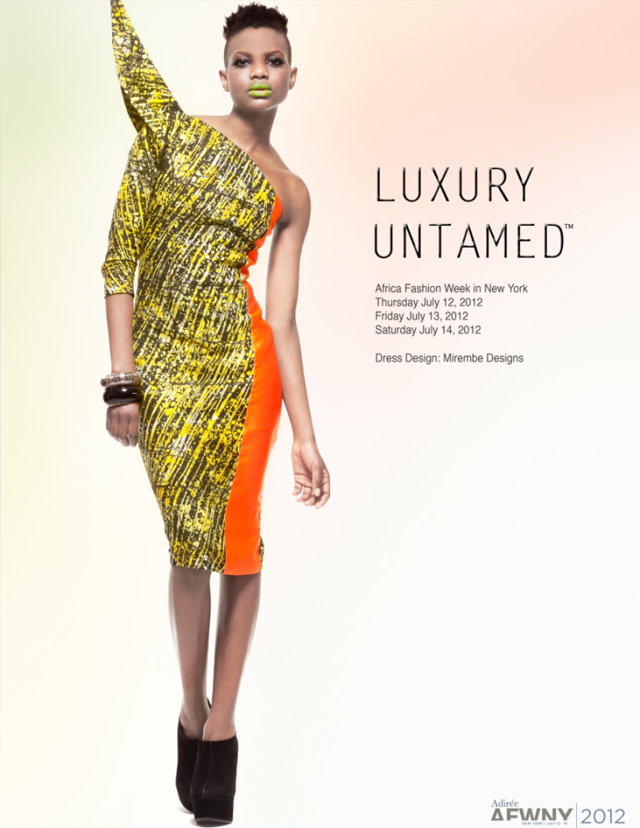

This unexpectedly fast rise leads the authors of the report to coin the term “super-luxury commodity” to refer to exclusive personal products (especially fashion and accessories) that carry enhanced transnational/transcontinental “portability” (catering to the habit of African elites to shop abroad), investment value, status symbol potential, and little or no tax implications. Among the top fashion male and female brands, New World Wealth’s survey lists Paul Smith, Hugo Boss, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Prada, Hermes, Canali. Interestingly, the list associates luxury with foreign goods and makes no mention of Africa-based providers of exclusive products. One of these is the Nigerian company Adirée, producer of Africa Fashion Week New York, which claims to “define some of Africa’s Fashion as synonymous with the word Luxury and as competitive in the luxury markets as European brands have been”.

Only a handful of the brands mentioned have mono-brand stores and operate mostly in the most sophisticated economies of Morocco and South Africa. Indeed, Bloomberg stresses that the continent is an “under-penetrated retail environment”. Looking at the impact of the existing semi-luxury and international fashion retailer market on the continent (like H&M), this observation prefigures that the economy and industry of exclusive taste will trigger major developments in Africa. As in any other instances of colonization, mega brands will have the chance not only of influencing taste choices and cultural judgments, but also of affecting the political and macro-economic policies of governments at the national and intra-regional level (something that I reference in my posts on the infrastructural changes brought about by the growth of the fashion industry in the Kenyan and Ethiopian East African regions).

Bloomberg analysts write that “spending on luxury goods in Africa is rising in-line with the expansion of wealth”, a misleading generalization if we consider other researches (see here and here for a more discursive approach to the narrative) contending that economic redistribution is not yielding promise, but actually increasing inequality among Africans. For example, in July the Guardian published the findings of a World Bank analysis that the number of poor people in Africa – defined as those living on less than $1.25 a day – actually increased from 411.3 million in 2010 to 415.8 millon in 2011. The International Monetary Fund has also reviewed its positive forecasts for most African countries for 2015 and 2016, citing fiscal retrenchment, high inflation, falling electricity supplies, job cuts in the extraction sectors for the unanticipated slow growth rates of South Africa, Ghana, and Zambia.

The data collected by market research firms corroborate the narrative of a booming African economy but fail to address the implications of this radical redistribution of global wealth in the hands of a shrinking few. The picture gleaned from these studies of the luxury market suggests that the growth of the market of super luxury fashion commodities will indeed accelerate the re-location of the hubs of taste-making and brand consolidation away from the West within contexts driven by aspirational dynamics and striking financial inequality.