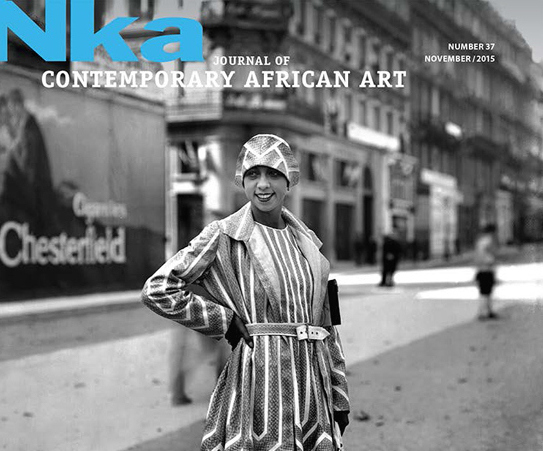

READING FILES: NKA SPECIAL ISSUE ON BLACK FASHION (PART 1)

NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art is out with a special issue on black fashion, featuring articles by eminent authors and artists. Its goal, as stated in the introduction by the editor Noliwe Rooks (Cornell University), is to approach the subject as “a launching point for thinking about race, gender, politics, powers, and class” (4). This is a good resource for anybody interested in black fashion and beauty that introduces the work of some of the leading voices in the field. Following is a detailed summary of the individual contributions.

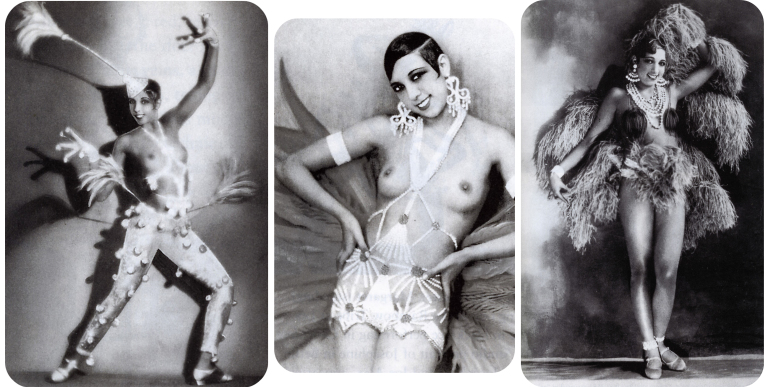

Anne Anlin Cheng (author of Jospehine Baker and the Modern Surface) discusses the concepts of “skin fashion” and “dressing race” in relation to Josephine Baker, whose theatricalised nakedness exposes skin not as essence but as “cover” (8) or surface. Chin’s argument is that, in the case of the African American diva, “We get bare/visible skin as metaphor, rather than as assumed materiality” (12). Accordingly, the article focuses on the paradoxes of phenomenology where visible skin fails to become an index of what the racial imaginations believes it stands for. The author examines Baker’s relationship with her skin through the trope of the house that the modernist architect Adolf Loos designed (but never built) for her. The house, – “a ‘dress’ for Baker” (12) – would be built around a two-storey transparent pool, which Chin regards as the scene of Baker’s self-conscious staging of nakedness. The architectural design is a simulation of the body, but also the imprint of that same body onto Loos’ imagination, the site of an epistemological crisis precipitated by a failure to see. “If Baker’s theatricalized nakedness offers a complex business about how difficult it is to be naked, then so does the interior of this house, designed to showcase this famous woman, itself embodies a cries about seeing – more accurately, a crisis about the mastery of seeing” (13). Chin’s use of the dress as trope of racial knowledge is an invitation to focus on dress as, literally, embodied matter and as an archive of the cultural consciousness of modernity.

In “Facing Tamara & Tireka”, photographer and scholar Bill Gaskin recalls the critical reactions to one of his most controversial shots, depicting two young African American women with their hair styled in the vertical fashion of Baltimore. The image was met with contempt by some members of the black public, who complained about the women’s looks. Gaskin argues that this reaction attests to the long-lasting effects of “the burden of … positive representation” (41) on the black community – the rule of always posing as dignified and respectable subjects for the photographer. The artist’s contribution stresses that hair styling is at the heart of black on black criticism, providing the normative framework to assess a person’s sense of collective responsibility and right to citizenship.

Monica Miller, author of the seminal text on black dandyism Slaves to Fashion (2009), discusses Janelle Monáe’s “tuxedo as a choice of uniform” (64) in an article that looks at its use in three videos by the artist. Miller holds that this sartorial choice exposes the tux as an “unstable” sign (64) and vital component of a radical aesthetic project: “In her carefully styled and executed ‘emotion pictures for the mind’, Monáe is determined to ‘flip the script,’ musically, sartorially, and categorically, in terms of identity” (68). The garment – a signifier of respectability and sobriety – is essential to the performance of inclusion – a reflection on freedom and oppression across gender, racial, and class lines – that Miller reads into the Monáe’s synergistic combination of visual and aural elements in her musical videos. “[H]er body and its tuxedo are worked in the service of revising oppressive histories and creating alternative futures” (64-65). The tux is a universal tool of reclamation for marginalised subjects, resisting categorisation at the level of phenomenology, the same level that produces commodified black bodies for the global visualscape: “Her ‘look’ does not fight her sound; instead, they complement each other, calculated to work together to respond to the currency and exploitation of black women’s bodies in the R&B and hip-hop marketplaces” (66). Ultimately, Miller writes that the tuxedo is a vehicle of self-knowledge, a way to conjure discipline and shape-shifting by, literally fitting oneself into a uniform. It “works as both a cover and a revelation for people and their embodied histories; when worn – and worked – it becomes ‘another way’ by which to fashion the self and progressive community” (68).

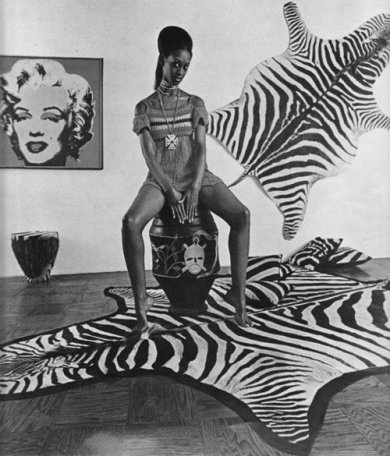

“The ‘Afro Look’ and Global Black Consciousness” by Tanisha Ford focuses on Afro-diasporic fashion of the 1960s and 1970s. In particular, Ford discusses the hybrid style adopted by South African socialities during the apartheid years that blended African and Western traditions.

The analysis, which draws on Ford’s work in her recently published book Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (2015), shows the historical value of the Afro look as one of many attempts by designers from the continent to claim modernity for themselves, discarding its hierarchical view of the world that placed the West – including its sartorial traditions – at the top of the evolutionary ladder. “Thus, the popularity of locally produced Afro-look garments … represented a reclamation of local textiles and sartorial techniques. This reclamation allowed African designers to destabilize the West-vs.-rest paradigm while also using the West as a point of comparison” (30). In this respect, the Afro look shows that fashion exploited the porous boundaries of national versions of racism to link the anti-apartheid struggle with the Black Liberation movement, becoming, not without contradictions, a versatile tool of affirmation. Indeed, Ford stresses that African models did not escape fetishisation and were often “used to reify a … construction of ‘blackness’ in which Africa is the pure and untouched motherland” (33). As in Miller’s study, the gender politics of the adorned body is a concern of the author, who insists that racial affirmation in the fashion market did not prevent the models from becoming objects, rather than subjects, of a Western gaze. Ford puts Africa’s contemporary appeal to fashion designers in a historical light, showing how, along with black America, the continent fully participated in the “black is beautiful” movement of the late 1960s, sharing in the tensions that ran through it. Further, the author looks at that decade of fashion through the lens of Drum, South Africa’s leading lifestyle magazine, offering a site-specific analysis of a heterogeneous and diversified phenomenon.

The two contributions by Helen Jennings (former editor of the Afropolitan lifestyle magazine Arise and author of New African Fashion [2011]) zoom in on the history of African fashion and some of its contemporary manifestations.

Her review of the photographic exhibition Haute Africa, held in Knokke-Heist (Belgium) in 2014, looks at how artists pursuing different agendas, including Martin Parr, Yinka Shonibare, Jehad Nga, Daniele Tamagni, iconise and code the style scenes from the continent into “a new discourse where art and fashion collide”(128). Jennings’ second contribution, “A brief history of African fashion”, is a virtual tour of Africa’s archive of sartorial traditions, where adornment and appearance have always “acted as advanced signifiers of status, ambitions, beliefs, and life stage” (46). As a fashion and style journalist, Jennings emphasizes Africa’s participation in global histories of trade and trend-setting and cites the ground-breaking work of tailors like Shade Thomas-Fahm (Nigeria), Alphadi (Niger) and Chris Seydou (Mali) that revolutionised African fashion in the second half of the 20th century. She also underlines that, in spite of the amount of innovation and creativity of such and many more figures, only a handful of these artists “have shared in the global fashion limelight alongside their Western counterpart” (50). Yet, Jennings observes, this trend is changing as a growing number of young creatives from the continent take advantage of the market’s thirst for “authenticity and unique goods” to promote a style born out of “clashing cultures and the crossing points of ethnicity in the modern world” (52). The outcomes are multiple, but they all not to “a freestyle wardrobe” for the independent subjects, using a variety of sources, including vintage couture fabrics and kaleidoscopic prints, to create “a delightful cacophony” of silhouettes (52).